There are times when sundry currents of information strike us at the same time, leaving us splashing in the roiled waters of our imagination. (Yes, I've been reading Rex Murphy again. Sorry about that.)

There are times when sundry currents of information strike us at the same time, leaving us splashing in the roiled waters of our imagination. (Yes, I've been reading Rex Murphy again. Sorry about that.)Nevertheless, today's Globe & Mail presents us with a series of images worth a comment or two. The first is of red water, with which those of us who have seen the recent trailer for The Reaping will be familiar. We learn from the Canada in Brief section that the Red River is rising in Selkirk, Manitoba because of an ice-jam, and, immediately adjacent to this report, we are informed of a leak at an Alcan factory near Jonquiere in Quebec, releasing bauxite sludge into the Saguenay River and causing stretches of it to turn red. Concerns have been raised about the effect of the spill on the environment, but an Alcan spokesperson assures us that there will be no ill effects, so I guess we can sleep tight.

This kind of odd juxtaposition can feed our primordial desire for meaning. End times, anyone? A compositor's decision with The Reaping as conscious or unconscious motivator? We look for order in chaos, and when flashes of order appear, we impose narratives--if you want proof, take a look at any conspiracy theory, such as the "inside job" of 9/11. The elements just seem to fit together, don't they? But that's what narrative does: it makes things cohere. On the positive side, it gives us order, however illusory; on the negative side, it can jam everything into one story--the so-called "grand narratives" that Jean-François Lyotard warns us to distrust. Or it can construct the closed delusional system of the paranoid, or of the conspiracy-mongering kerosene-and-rabbit-wire nutbar.

Which brings me, by a circuitous route, to theocracy. The impulse behind religion--the experience of the spiritual, the sense of wonder, the intuitive awareness of the interconnectedness of all things--is transmogrified almost inevitably into a set of rules and admonitions, an order imposed by force. The haunting poetry of al-Rumi turns into the ossified, hateful and simplistic dogma of the Salafist. According to one account,Christ danced with his disciples in the garden of Gethsemane (Acts of John 94-96), but the powers that be wouldn't let that one into the canonical Bible. Popes don't dance: they condemn millions to death in Africa with their opposition to condoms, and their priests destroy the lives of countless children who venture too close to them. The ecstatic William Blake, as always, says it best:

I went to the Garden of Love,

And saw what I never had seen;

A Chapel was built in the midst,

Where I used to play on the green.

And the gates of this Chapel were shut

And "Thou shalt not," writ over the door;

So I turned to the Garden of Love

That so many sweet flowers bore.

And I saw it was filled with graves,

And tombstones where flowers should be;

And priests in black gowns were walking their rounds,

And binding with briars my joys and desires.

So long as the spiritual is hijacked by the likes of Osama bin Laden, Benedict XVI and the countless Pat Robertsons, Jerry Falwells and Jimmy Swaggarts of this world, not to mention George Bush and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, we shall have nothing but rods of iron and holy wars. And rivers running red with blood.

Turning now to allophilia, with a hat-tip to the Globe's Sheema Khan, we have a professor at Harvard looking at social cohesion in a new way. Instead of "tolerance" of differences, and figuring out how to deal with xenophobia, Professor Todd L. Pittinsky thinks that we should be promoting and cultivating a positive liking for other groups. What a concept! But a word of warning--someone else tried that a couple of millennia back, and we're observing the anniversary of his execution this very weekend.

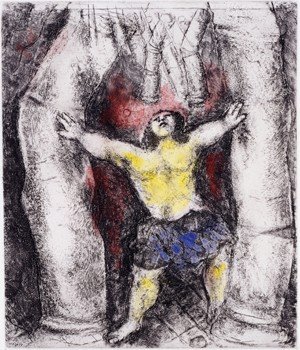

And finally, back to where I started--with yet another florid, over-wrought column by Rex Murphy. Today he's exercised because Handel's Samson oratorio is being given "a modern political reading" by an artistic director in Victoria. Samson is being portrayed as a suicide terrorist, which doesn't work for Murphy because the strong man has the wrong religion, and because the artistic director has the wrong politics, a sin that Murphy, with no visible trace of irony, attempts to rebut with political arguments of his own, when he isn't personally attacking the director. But then we come to this: "This insertion of current politics into timeless masterpieces is a form of petty vandalism."

That one took my breath away. Because Murphy is here arguing, not for art, but for religion. What, after all, is a "timeless masterpiece?" Has the man never been to Stratford, to witness the endless interpretations, many of them good, of William Shakespeare's plays? Does the strength of art not lie precisely in its capacity to be endlessly reinterpreted, made real and immediate for audiences across centuries and cultures? Its "timelessness" consists of its almost infinite adaptability, not its persistence as one thing while history and culture eddy around its vast, immoveable bulk. The latter isn't art--it's just another version of that vulgar notion of God that's causing so much trouble. It stems from the self-same desperate clinging to the authority and stability and order that totalitarians promise. It is founded on fear and self-deception, and there is no shortage of politicians and preachers to exploit both for their own ends.

Samson Agonistes, John Milton's poem upon which Handel based his work, is only intelligible to us today because we recognize the emotions and the images that it conjures up: the heroic representative of a people, captured, blinded and enslaved, who sacrifices himself in order to kill his enemies, delivering his people from the "Philistian yoke" and thus carrying out the will of God. In a place called Gaza. Attempting to discern his all-too-human psychology in the poetry, we might well develop a different, and deeper, insight into the mind of a suicide bomber, or a young kid at Vimy, for that matter, fighting the war to end all wars. Battles are at this very moment raging over Samson's grave. We can be stirred by this poem for numerous reasons, centuries after it was written--but not if we treat it as holy writ, timeless and unchanging, and wait for it to be interpreted for us by imperious clerks, high priests and newspaper columnists. The letter killeth.

1 comment:

It's an remarkable post for all the online visitors; they will obtain advantage from it I am sure.

my homepage :: lowes large appliances

Post a Comment